Slayton Evans Memorial Lectureship

Professor Slayton Evans Jr. was born in Chicago, IL, in 1943 but spent his childhood in Meridian, Mississippi. Upon moving south, the Evans’ family lived in a segregated public housing project and Slayton and his younger brother and sister attended a segregated Catholic School. Slayton helped pay for his school tuition by mowing lawns and by working as a junior assistant janitor at his elementary school. His interest in chemistry began early, when he was given a chemistry set. In addition, a small microscope allowed him to study and draw various plant specimens and insects. In a number of interviews, Slayton describes the launch of the Sputnik satellite as a transformative moment in his early life. Soon after, he found a book about rocketry in the library and went about making his own dry rocket fuel to launch homemade rockets. Slayton’s initial plan was to enlist in the Air Force with the goal of eventually becoming an astronaut, but his height disqualified him from flight training. Instead, he was able to secure both an academic and athletic scholarship to cover his higher education at Tougaloo College.

Testing

[iframe width=”640″ height=”360″ src=https://vimeo.com/853871079/f977c93866?share=copy frameborder=”0″ allow=”autoplay; encrypted-media” allowfullscreen][/iframe]

As an undergraduate student at Tougaloo College in Jackson, Mississippi, Slayton met and was influenced by The Freedom Riders, as they and subsequent participants would come to be known. The Freedom Riders took a bold non-violent stand against segregation. As a historically black liberal arts college, Tougaloo became a rallying place for Freedom Riders because its status as a private college allowed protection from invasions by anti-civil rights organizations.

During his time in college, two internships at Abbott Laboratories in Chicago solidified Slayton’s desire to be a research chemist. He entered graduate school at Case Western Reserve University with the necessary financial aid provided by a research assistantship. In a fortunate turn of events, his graduate project investigating a medication for a parasitic disease common to Southeast Asia was deemed crucial to the war effort in Vietnam and allowed him to defer his draft notice.

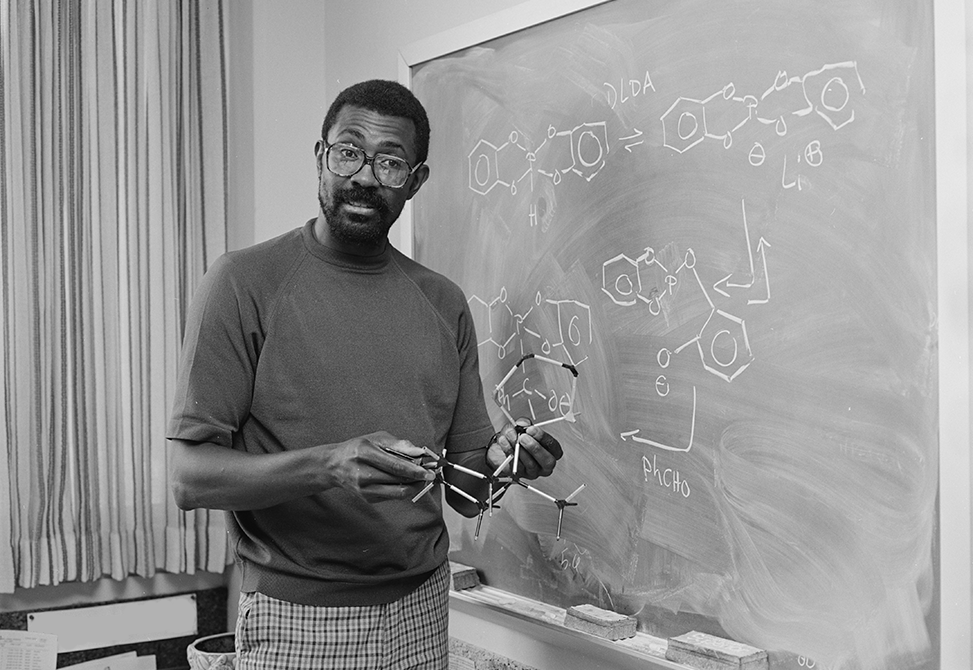

In 1970 Dr. Evans joined renowned chemist Ernest Eliel at the University of Notre Dame for a postdoctoral position studying stereochemistry and conformational analysis of small organic molecules. After his time at Notre Dame, Dr. Evans accepted a position at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. At around the same time, Professor Eliel moved to UNC Chapel Hill as the W. R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Chemistry and sought to recruit his former postdoc to join the department. With the opportunity to continue a research career at a larger university, Professor Evans joined UNC Chapel Hill as an assistant professor in 1974, becoming the first black chemist in the Department’s now 200-year history.

Professor Evans had a long and successful career at UNC Chapel Hill. He rose to the rank of professor in only 10 years and established a legacy of excellence in both mentoring and science. His scientific contributions focused on organophosphorus chemistry, especially for asymmetric synthesis and conformational analysis. His asymmetric synthesis of alpha-amino phosphonic acids using sulfimides as directing groups stands as a landmark contribution to the field (J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 7532.). His experimental work was known for its depth. Jeff Kelly, a student of Prof. Evans and currently the Lita Annenberg Hazen Professor of Chemistry at the Scripps Research Institute, said “Slayton was a model professor. He had very high standards and demanded excellence from his students. I would not be in academia today had I not been mentored by Slayton Evans.” For his scientific contributions, Prof. Evans was awarded the 1995 Special Creativity Award in Organophosphorus Chemistry from the NSF. His expertise was also highly sought after by national and international organizations; he established international collaborations in France, Mexico Germany, Greece and Russia. He served in advisory roles for the NSF, NIH, and as chair of the U.S. National Committee of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC).

Professor Evans was also known as an excellent mentor who was deeply committed to recruiting and championing minority students. He strived to make complex subjects accessible to undergraduates and relished one-on-one mentoring relationships with undergraduate and graduate students alike. Derrick Tabor, Prof. Evans’s first Ph.D. student and now a program director at the NIH National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, said: “He had a wonderful gift for making undergraduate students, graduate students and his friends and colleagues feel special.” His colleague Ed Samulski recalls, “Slayton was extraordinarily diplomatic, perhaps because he like all African-Americans knows the damage that harsh words and thoughtless behavior can do to the human being. Therefore, he was careful never to slight anyone with words. It is no accident that he was totally dedicated to teaching and to his students. He wanted to nurture them, not to show them how smart he was.” For his prodigious efforts in education and promoting diversity, Prof. Evans was honored with the UNC Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Education, the UNC Tanner Award for Teaching Excellence, and the ACS Award for Encouraging Disadvantaged Students into Careers in the Chemical Sciences.

Professor Evans passed away in 2001 at the age of 58 years old. As a testament to Professor Evans’s legacy, donations flooded in to endow the Slayton Evans Jr. Memorial Fund, which supports the visit of a preeminent speaker in the chemical sciences each year. Recently, the Slayton Evans Memorial Lecture has focused on specifically highlighting the contributions of diverse chemists and is coupled with an outreach program that brings undergraduate students from traditionally underrepresented backgrounds to UNC for the day. This annual event, along with the lasting influence he had on science, his trainees, and his colleagues, has kept the remarkable life and legacy of Professor Evans shining bright.