Kara Joseph Wins NSF Fellowship for Research on PFAS in Marine Mammal Milk

A key part of Kara Joseph’s research is looking at how PFAS transfer from mother to baby over time, especially in comparing first-time mothers to mothers who’ve had multiple babies. Scientists think that a first baby might get a bigger dose of PFAS, because the mother has had her whole life to accumulate the chemicals.

May 2, 2025 I By Dave DeFusco

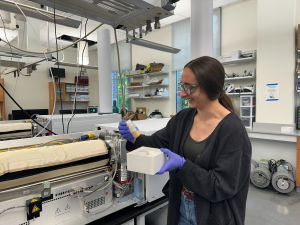

Kara Michelle Joseph, a Ph.D. student in UNC’s Department of Chemistry and a member of Dr. Erin Baker’s lab, has won one of the nation’s top awards for young researchers, the 2025 National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, for her work investigating how toxic “forever chemicals,” called PFAS, are passed from marine mammal mothers to their babies through milk.

PFAS, short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are synthetic chemicals that have been used since the 1950s in products like non-stick pans, waterproof clothing and firefighting foam. They’re often called “forever chemicals” because their strong carbon-fluorine bonds make them extremely hard to break down. As a result, PFAS have spread across the planet—into the water, soil, air and living creatures—and don’t go away easily.

Once inside animals or humans, PFAS build up over time, getting passed along the food chain to predators like dolphins, seals and whales. Research shows PFAS can harm the immune system, slow growth and development, interfere with reproduction and affect how bodies manage fat. But while scientists have studied how PFAS behave in humans, they know far less about how other mammals, especially marine mammals, process these chemicals.

That’s where Joseph’s research comes in. At first, she thought about studying a wide range of animals, including land mammals. But after getting feedback from her peers and mentors, she decided to focus on marine mammals. There were two big reasons: Marine mammals are especially vulnerable to pollution because they live at the top of the food chain, where PFAS concentrations are highest, and her collaborator at the Smithsonian had an impressive collection of marine mammal milk samples, a rare and valuable resource.

“Marine mammals are really susceptible to environmental contaminants,” said Joseph. “And getting samples from them is much harder than from land animals, so there’s a real need for more research.”

One major challenge Joseph faced was that marine mammal milk is very different from cow’s milk or even human breast milk. Cow’s milk has about 3% to 4% fat. Marine mammal milk, by contrast, can have up to 15% fat. Very few researchers had ever tried to measure PFAS in such fatty milk before.

“The biggest struggle was trying to adapt methods designed for much lower-fat samples,” she said.

Using a technique called LC-IMS-MS (liquid chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry–mass spectrometry), Joseph can separate and detect tiny amounts of PFAS even when they’re hidden in complex biological samples like milk. She also helped expand her lab’s database of known PFAS, which allows her to find both familiar and emerging PFAS compounds that haven’t been well-studied yet.

Through her work, Joseph has already made some surprising discoveries. Not only is she finding common PFAS compounds in marine mammal milk, but she’s also seeing “branched” versions of these chemicals, which are slightly different forms that could have different biological effects. Even more surprising, she and a fellow student are discovering lots of unknown fluorinated compounds—chemicals that shouldn’t necessarily be there, especially considering that some of the samples are more than 30 years old.

“There’s a lot more than we thought would be in them,” said Joseph.

Another key part of Joseph’s research is looking at how PFAS transfer from mother to baby over time. She’s especially interested in comparing first-time mothers (primiparous) to mothers who’ve had multiple babies (multiparous). Scientists think that a first baby might get a bigger “dose” of PFAS, because the mother has had her whole life to accumulate the chemicals. If a lot of PFAS leaves the mother’s body during that first pregnancy and nursing period, later babies might be exposed to smaller amounts.

While Joseph’s work is still ongoing, this research could have important implications for how scientists understand toxic chemical risks across generations, not just for marine mammals but potentially for humans.

“Kara has driven this project from its initial stages, by first finding the milk samples from the Milk Repository at the Smithsonian, to performing the contaminant analyses,” said Dr. Baker, who is Joseph’s PhD. advisor. “Her drive to thoroughly explore these milk samples will ultimately enable our understanding of lactational exposure to babies and potential needs for remediation efforts to reduce or eliminate this multigenerational transfer of contaminants.”

Dr. Baker said that, ultimately, Joseph’s project could influence how scientists, conservationists and policymakers think about protecting wildlife and humans from chemical pollution. The work also supports national efforts to better study and regulate PFAS, aligning with the PFAS Federal Research and Development Strategic Plan.

“My goal is to share this information directly with wildlife biologists and conservationists who can implement changes quickly,” she said. “By working with recognizable, public-facing animals like dolphins and seals, I hope my research will raise awareness of the widespread dangers of PFAS, and inspire more action to protect our ecosystems.”