UNC Researchers Pioneer Light-Powered Technique to Enhance PET Scan Disease Detection

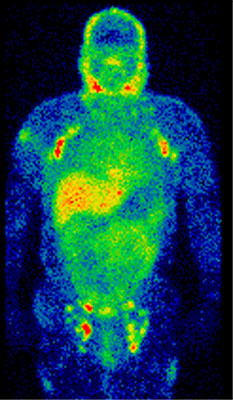

For decades, doctors have used positron emission tomography (PET) to peer inside the human body, detecting diseases like cancer, Alzheimer’s and heart conditions before symptoms even appear. PET scans rely on tiny amounts of radioactive material, called radiotracers, to highlight areas of concern.

March 19, 2025 I By Dave DeFusco

For decades, doctors have used positron emission tomography (PET) to peer inside the human body, detecting diseases like cancer, Alzheimer’s and heart conditions before symptoms even appear. PET scans rely on tiny amounts of radioactive material, called radiotracers, to highlight areas of concern. But behind every scan is a complex and time-sensitive chemical process to create these tracers—a process that has long been slow, expensive and inefficient.

In a study published in Nature Chemistry, “Arene Radiofluorination Enabled by Photoredox-mediated Halide Interconversion,” co-authors Dr. David Nicewicz, William R. Kenan, Jr. Distinguished Professor in the UNC Department of Chemistry, and Dr. Zibo Li, a professor in the UNC School of Medicine, have developed a promising method to make radiotracers faster, more efficiently and with less waste. Their new approach, called photoredox-mediated arene radiofluorination, uses light to simplify the process of attaching radioactive fluorine to molecules used in PET scans. This innovation could radically improve medical imaging, making PET scans more accessible and precise.

“Imagine a doctor trying to find a single malfunctioning lightbulb in a massive city grid,” said Dr. Nicewicz. “Without the right tools, it would take forever to pinpoint the exact problem. That’s similar to how traditional imaging methods struggle to detect diseases at their earliest stages. PET scans, however, act like a spotlight, illuminating specific cells or biochemical processes that indicate disease.”

Here’s how it works:

- A radiotracer is injected into the body. The most common one, FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose), is a sugar-like molecule tagged with radioactive fluorine-18.

- The tracer travels through the bloodstream and attaches to specific cells—often cancerous ones, which consume more sugar than normal cells.

- A PET scanner detects the radiation and creates a detailed image, showing areas where the tracer has collected.

This technology has transformed how doctors diagnose and treat illnesses, but the process of making these radiotracers has been a bottleneck. Radiotracers must be made quickly and precisely. Since fluorine-18 has a half-life of less than two hours—meaning it loses half of its radioactivity every 110 minutes—scientists are racing against the clock. Any delay or inefficiency means less usable material and wasted resources.

Traditional methods for attaching fluorine-18 to molecules involve harsh chemicals, high temperatures and multiple steps. It’s a tricky process and, often, scientists can’t modify complex molecules without ruining their structure. This limits the number of PET tracers that can be developed, slowing progress in medical imaging.

Enter photoredox-mediated arene radiofluorination. Instead of relying on extreme heat and aggressive chemicals, this method uses visible light and special catalysts to drive the reaction. The process is gentler, more controlled and works on a wider range of molecules.

As a result, it’s faster. The reaction happens more quickly than traditional methods, meaning more radiotracers can be produced in less time. It’s more efficient. Less starting material is wasted, which reduces costs and increases the amount of usable product. And it works on more molecules. This flexibility could help scientists design new PET tracers for diseases that currently lack good imaging tools.

The breakthrough was made possible by advancements in photoredox catalysis—a technique that uses light to power chemical reactions. By fine-tuning this approach, researchers found a way to attach fluorine-18 to molecules with incredible precision.

This innovation could open the door to a new generation of PET tracers, improving how we detect and track diseases. Some potential benefits include:

- Earlier cancer detection. More sensitive tracers could help doctors find tumors when they’re still tiny and easier to treat.

- Better brain imaging. Diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s could be diagnosed earlier, allowing patients to receive treatment sooner.

- Personalized medicine. PET scans already help doctors tailor treatments based on how a patient’s body responds—better tracers could make this even more precise.

Beyond medicine, this technology could also have applications in drug development, helping pharmaceutical companies test new treatments more effectively. While this discovery is a huge step forward, there’s still work to be done. Scientists need to refine the process, scale up production and test how these new tracers perform in real-world medical settings. But the potential is undeniable—this light-powered approach could transform how PET imaging is used in hospitals and research labs worldwide.

“For patients, it means more accurate diagnoses, better treatment options and a future where diseases are caught earlier than ever before,” said Dr. Li. “And all of this, thanks to a little bit of chemistry and the power of light.”