UNC Researchers Create Low-Cost Antibody Test Using Common Glucometers

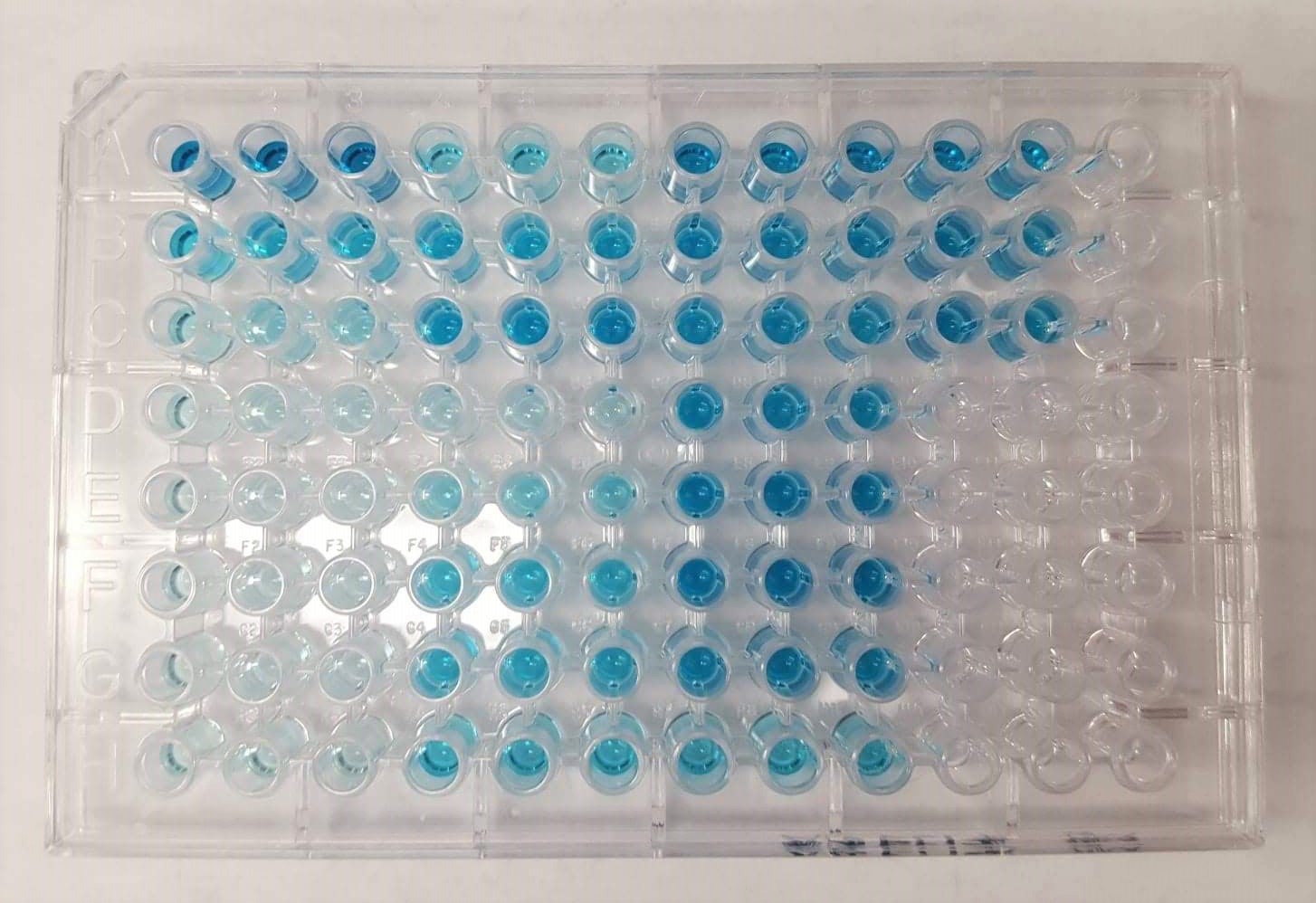

A study, led by Associate Professor Netz Arroyo and published in Sensors & Diagnostics, focuses on improving a new kind of antibody test that the team created in earlier research. Traditional antibody tests, known as ELISAs, above, rely on enzymes such as horseradish peroxidase to produce a color change that reflects how many antibodies are present. Since ELISAs are difficult to use routinely or at large scale, especially in places with limited resources, the researchers asked themselves whether they could turn antibody testing into something as easy and affordable as checking a person's blood sugar.

January 9, 2026 | By Dave DeFusco

Scientists at UNC-Chapel Hill have developed a new way to measure antibodies using the same inexpensive glucometers that millions of people use every day to monitor blood sugar. The work, led by Netz Arroyo, an associate professor in the Department of Chemistry, adapts a highly technical laboratory method into a format that could one day help public health officials quickly assess immunity across large populations.

Their study, published in Sensors & Diagnostics, focuses on improving a new kind of antibody test that the team created in earlier research. Traditional antibody tests, known as ELISAs, rely on enzymes such as horseradish peroxidase (HRP) to produce a color change that reflects how many antibodies are present. Reading that color change, however, requires a specialized spectrophotometer, an expensive instrument usually found only in research labs or hospitals. As a result, ELISAs are difficult to use routinely or at large scale, especially in places with limited resources.

“We asked ourselves a very simple question,” said Arroyo. “What if we could turn antibody testing into something as easy and affordable as checking your blood sugar?”

To do that, Arroyo’s team partnered with the Spangler lab at Johns Hopkins University to design a genetically engineered fusion protein called LC15. Instead of using HRP to generate a color change, LC15 includes two units of an enzyme called invertase, which converts sucrose, or table sugar, into glucose. Because glucometers read glucose levels instantly, the amount of glucose produced by LC15 becomes a direct measurement of how many antibodies are in a sample. Importantly, the LC15 protein is built with precise, one-to-one control of how much enzyme is attached to each antibody, allowing for exact antibody concentrations rather than the approximate “titer levels” that commercial ELISAs provide.

“Absolute quantification matters,” said Arroyo. “If you want to dose convalescent plasma or compare antibody levels across different treatments, you may need a real number, not a relative score.”

In earlier work, the team demonstrated that LC15 could be used to measure antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 virus using small plastic strips, but those strips were tedious to prepare and could only handle a limited number of samples at a time. For large studies, or for public health departments that might test hundreds of samples a day, this setup wasn’t practical.

The new paper solves that problem by adapting the test to 96-well microwell plates, a common laboratory format that allows dozens of samples to be processed in parallel. The researchers optimized the pH, fine-tuned reagent amounts and adjusted other conditions to make sure the test still worked with the new layout.

“We were able to maintain the same sensitivity as the original strip-based test,” said Arroyo, “but we cut reagent use five-fold and increased the number of samples we could analyze in a single run. It makes the entire workflow faster, cheaper and much easier to scale.”

The team validated the updated test using the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein—the same viral protein targeted by most COVID-19 vaccines—as the bait for capturing antibodies. They screened 72 clinical plasma samples and compared the results to those from commercial ELISAs in a blinded study. The correlation was strong across a wide range of antibody concentrations, showing that the new system performs comparably to traditional lab equipment.

The biggest advantage, however, may be accessibility. Because glucometers are inexpensive, portable and already integrated into telehealth and electronic medical systems, they could allow antibody testing to move out of specialized labs and into clinics, pharmacies or even homes.

“Glucometers are everywhere. They’re FDA-approved and very reliable, and people know how to use them,” said Arroyo. “By building our assay around a device that already exists at massive scale, we’re opening the door to population-level immunity monitoring.”

That kind of monitoring could be invaluable during future outbreaks, allowing health officials to understand in real time how immunity levels are changing and where resources need to be directed. It could also help in areas without access to expensive lab instruments, making high-quality antibody testing more globally equitable.

The current version still requires reading each well individually with a handheld glucometer, which takes time, and because invertase continues producing glucose during measurement, the researchers must use calibration steps to adjust for “drift” as glucose levels slowly rise. Even so, the method consistently produces accurate results.

“Every tool has tradeoffs,” said Arroyo, “but the combination of accuracy, affordability and accessibility we’ve achieved here is extremely promising. Our goal is to build diagnostic tools that the world can actually use, not just in well-funded labs, but everywhere.”

An ELISA test performed in a 96-well plate, where a common enzyme (horseradish peroxidase) reacts with a chemical solution to turn the liquid blue, showing that antibodies are present.