Ph.D. Student Uses Machine Learning to Transform Gene Therapy Production

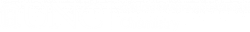

Ph.D. student Kelvin Idanwekhai is using machine learning to transform how viruses—the microscopic couriers of genetic medicine—are purified, making the process faster, cheaper and more precise.

January 9, 2026 | By Dave DeFusco

The future of gene therapy may not lie in the lab bench but in the algorithm. At UNC-Chapel Hill, chemistry Ph.D. student Kelvin Idanwekhai, who presented his research at the Triangle Student Research Competition, is using machine learning to transform how viruses—the microscopic couriers of genetic medicine—are purified, making the process faster, cheaper and more precise.

He works with a type of artificial intelligence called Gaussian Processes and a method called Bayesian Optimization. These tools are designed to help scientists explore complicated problems efficiently, especially when they have too many variables to test one by one.

“In chemistry and bioprocessing, people often rely on design-of-experiment methods,” said Idanwekhai. “Those work fine when you’re dealing with a small number of parameters. But when you’re trying to adjust 10 or more things at once, like pH, salt concentration, temperature and flow rate, it becomes impossible to test everything manually.”

That’s where machine learning comes in. Instead of trying every possible combination, Idanwekhai’s algorithm “learns” which experiments are most likely to yield good results and tests only those. Over time, it uses what it learns to predict even better outcomes.

To test this approach, Kelvin applied his system to one of the most promising areas of medicine: gene therapy. Gene therapy uses harmless viruses to deliver healthy genes into a patient’s cells. The virus acts like a delivery vehicle, carrying the genetic material where it’s needed. Among these delivery vehicles, adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are among the safest and most effective. Producing AAVs, however, is expensive and complex.

One of the hardest parts is purification, or removing unwanted and damaged particles without harming the virus itself. This process involves several steps of chromatography, a method for separating substances. Each step requires precise control of multiple factors, such as buffer composition, pH and flow rate. Traditionally, scientists have optimized these steps through trial and error.

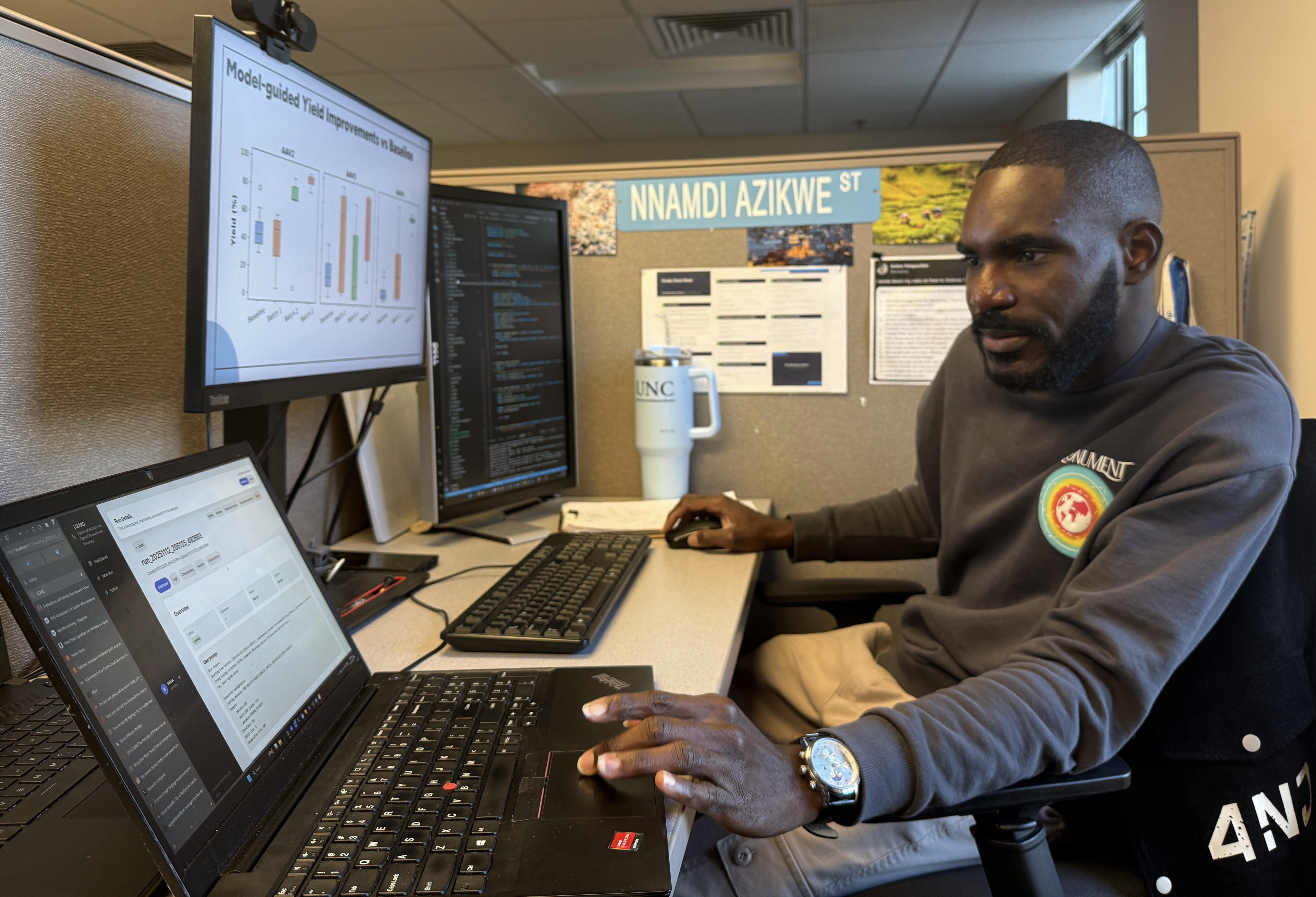

Idanwekhai wanted to replace that slow, empirical process with something smarter. “With Gaussian Processes and Bayesian Optimization, we can explore a search space that might include 900,000 possible experiments,” he said, “and we can find an optimal set of parameters we need in just 30.”

In his study, Idanwekhai and his collaborators in Stefano Menegatti’s lab at North Carolina State University applied this method to optimize purification for three different AAV serotypes—AAV2, AAV5 and AAV9. Each behaves a little differently at the molecular level. Still, Idanwekhai’s model handled them all. After just three rounds of optimization, the team increased viral yields from 70% to 99% while cutting impurities and preserving the viruses’ biological activity.

The key, said Idanwekhai, was the kernel, the mathematical heart of the Gaussian Process that determines how the model represents data. “I tested a lot of models, but the custom kernel I designed gave the best accuracy,” he said. “That’s what really drove the optimization gains.”

Another strength of Idanwekhai’s approach is interpretability. Traditional machine learning models act like “black boxes”; they give predictions without explaining why. Gaussian Processes, on the other hand, can show which variables matter most. “You can look inside the model and see, for example, that pH has the biggest effect on yield,” said Idanwekhai. “That gives you both speed and insight.”

The results were impressive not only for their efficiency but also for their transferability. Data from the AAV2 experiments helped seed the optimization process for AAV9, cutting the number of tests needed to achieve high yields. “We saw that learning could transfer between serotypes,” said Idanwekhai. “That means the model wasn’t just memorizing, it was understanding.”

Behind the scenes, however, the project faced practical challenges. Most laboratory machines don’t easily share data. He hopes future lab equipment will include simple ways to connect with computer systems so that experiments can truly run in a closed loop, where data flow automatically from the instruments to the AI and back again.

“A lot of experimental data are stuck in the instruments themselves,” said Idanwekhai. “I had to go to the machines and extract the data manually. It took months.”

Looking ahead, Idanwekhai envisions integrating reinforcement learning and large language models, like those behind chatbots, into future systems. These tools could read scientific papers, understand previous results and suggest smarter experiments. His lab has already started developing an AI platform called LIZARD (Ligand optimization via agentic research and discovery), designed to autonomously search for and optimize potential drug molecules.

“We’re building a software tool called BASIL that lets lab scientists use the same approach we used in the AAV project without needing to write code or understand how to build computer models,” said Idanwekhai. “Our other collaborations are doing something similar. We’re using AI and machine learning to help guide experiments in real time and make the research process faster and more efficient.”

Under the guidance of Professor Alexander Tropsha, Idanwekhai said he’s found the perfect environment to innovate. “Dr. Tropsha really values independence,” he said. “He tells us, ‘Your Ph.D. is not my Ph.D.’ That freedom lets me chase ideas I believe in.”