Emmy Tang Studies Cancer Drugs That Could Also Treat Rare Blood Disorders

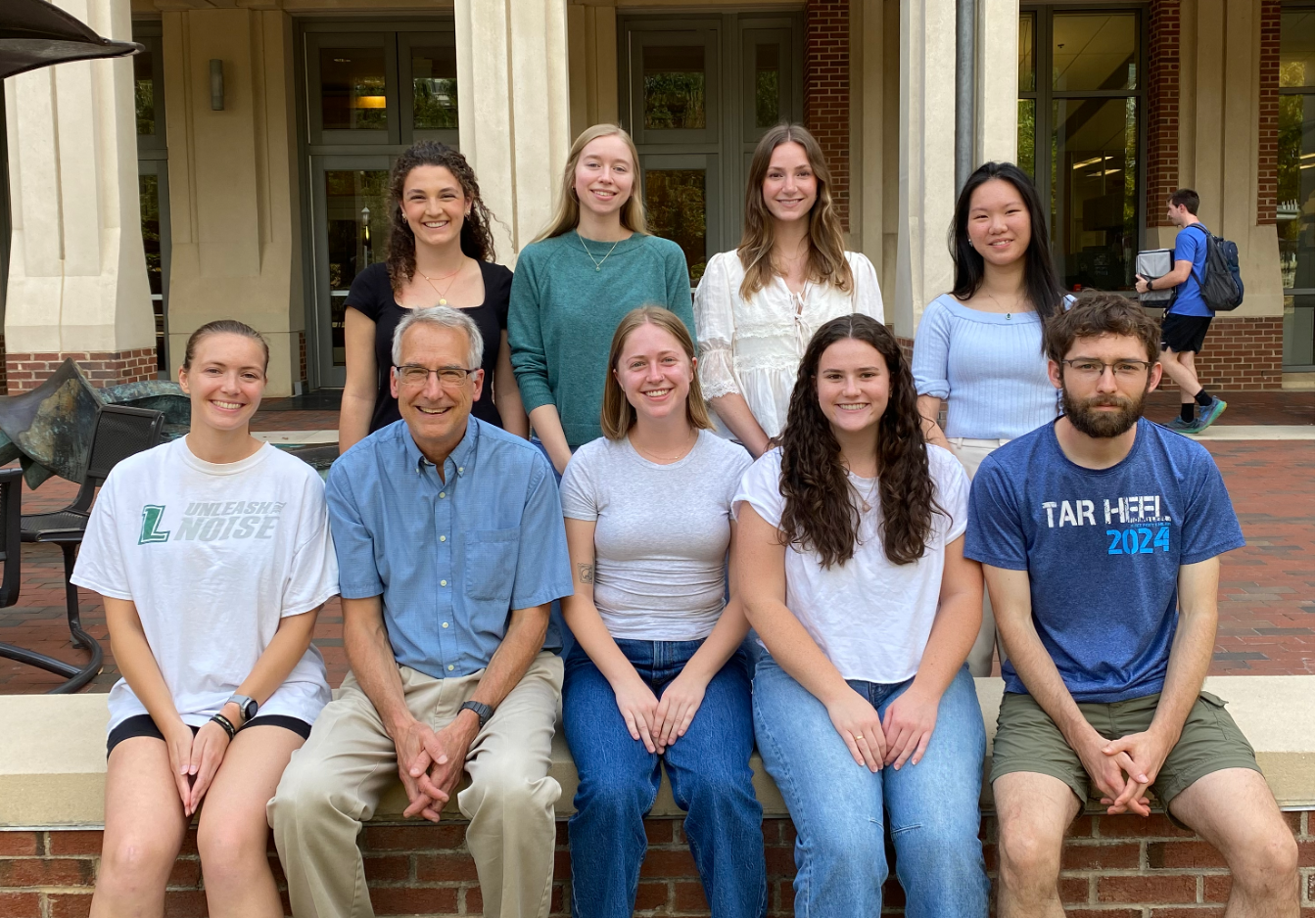

Under the guidance of Dr. Lee Graves, a professor known for his research in pharmacology and drug development, Emmy Tang, back row far right, has developed her own project investigating how cancer drugs work in the context of a rare disease called porphyria.

October 23, 2025 I By Dave DeFusco

When Emmy Tang arrived at UNC-Chapel Hill, she didn’t picture herself handling cancer cells or running multiday experiments. In fact, when she first joined the Graves Lab in the UNC School of Medicine’s Department of Pharmacology, her job was to wash dishes and sterilize lab equipment. But that humble beginning turned out to be the first step toward a hands-on research career.

“I started as a work-study assistant, just autoclaving and dishwashing,” said Tang, now a third-year chemistry major. “But my grad student mentors, Sabrina Daglish and Owen Canterbury, began showing me how to do things like Western blots and tissue culture. I also saw the senior undergrads doing real experiments, and I wanted to be like them. So that’s how I stayed the course.”

Under the guidance of Dr. Lee Graves, a professor known for his research in pharmacology and drug development, Tang has developed her own project investigating how cancer drugs work in the context of a rare disease called porphyria.

“I didn’t really know much about porphyrias until Dr. Graves explained how they connect to our research,” she said. “Porphyrias are rare metabolic diseases that affect the body’s ability to make heme, the molecule needed to produce hemoglobin in red blood cells. Because of mutations in the heme-making pathway, toxic intermediates build up in the body, which can cause skin sensitivity, blisters and other problems.”

The name porphyria comes from porphyrins, molecules that resemble chlorophyll—the green pigment in plants—but in this case, they collect in human tissue. When exposed to sunlight, they react and damage the skin. Tang’s project focuses on proteins in this pathway and how certain cancer drugs might affect them.

One drug she investigates is ONC201, recently approved by the FDA for treating a type of childhood brain cancer called glioma. In the lab, Tang and her lab mates study similar compounds, known as TR compounds, that target a structure inside cells called the mitochondria, the cell’s energy factory.

“These drugs activate a protein called ClpP,” said Tang. “It’s basically a tiny shredder for unwanted proteins. Our drug acts like a key that turns it on, helping it chew up certain proteins that cancer cells need to survive.”

The Graves lab has already shown this protein degradation can stop breast cancer cells from growing. Even more interesting, one of the proteins that gets destroyed is the first enzyme in the heme synthesis pathway, suggesting that these drugs might also help treat porphyrias someday.

To test this, Tang spends long hours culturing cancer cells, treating them with drugs and measuring the results using a method called Western blotting. “You grow the cells, treat them and then break them open to see what’s happening inside,” she said. “A Western blot lets you see which proteins are still there after drug treatment. If the band for that protein disappears, it means the drug broke it down.”

Each experiment can take several days, with Tang returning to the lab at specific time points to collect samples. “It’s very time-intensive,” she said. “Sometimes you have to come back after three hours, six hours or even the next day.”

Balancing this research with a full class schedule has been one of her biggest challenges. “Time management has become an art,” said Tang. “But I’ve learned to plan carefully, write out how long things will take and communicate with my lab partners and mentors. It helps that my PI is very hands-on. Sometimes he even helps with the experiments.”

Through it all, she credits her mentors with shaping her scientific confidence. “Sabrina and Owen taught me everything from scratch,” she said. “Now I can troubleshoot on my own, but I still learn by watching them solve problems. They’ve really gotten me where I am today.”

As she looks ahead, Tang hopes to pursue a Ph.D. or possibly an M.D.-Ph.D. program, continuing her passion for discovery. “This has been a pillar experience in my undergraduate career,” she said. “I want to keep doing bench work, asking questions and maybe publish a paper with my lab. It’s hard work, but it’s also really exciting to be part of something that could one day help patients.”