October 8, 2025 | By Calley Jones, College of Arts and Sciences

On Tuesday, Oct. 7, Frank Leibfarth spent the evening at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, 501 miles from his home base in Carolina’s Caudill Labs.

That’s slightly farther than the combined length of the Deep River, the Haw River and the Cape Fear River that form a unified watershed serving more than 1.5 million North Carolinians. It’s the largest river basin in North Carolina.

It’s also among the most polluted.

Leibfarth’s innovative solution to help remove toxic chemicals from the Cape Fear River Basin was among many reasons he was in New York at a celebration hosted by the Blavatnik Family Foundation and the New York Academy of Sciences. There, he was named the 2025 Blavatnik National Awards for Young Scientists Laureate in the Chemical Sciences, an award that comes with a $250,000 prize.

Inspired by the Nobel Prizes, the Blavatnik National Awards for Young Scientists are the largest unrestricted prizes for early-career researchers in the United States. Leibfarth joins two other 2025 Laureates — Philip J. Kranzusch from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, who won the prize in the life sciences category, and Elaina J. Sutley from the University of Kansas, who won the prize in the physical sciences and engineering category.

This year’s laureates were selected from a pool of 310 nominees representing 161 academic and research institutions across 42 states. The award is “designed to empower them with the freedom to continue to explore bold ideas, driving scientific innovation forward,” said Len Blavatnik, head of the Blavatnik Family Foundation.

“We are tremendously proud of Professor Leibfarth for this well-deserved recognition of his groundbreaking work in the chemical sciences,” said Chancellor Lee H. Roberts. “Being named a Blavatnik laureate is an extraordinary achievement and a historic first for Carolina, reflecting the far-reaching impact of his research and innovation.”

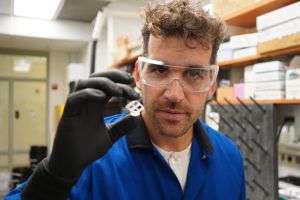

Leibfarth, the Royce Murray Distinguished Term Professor of Chemistry and the inaugural Institute for Convergent Science faculty fellow, was awarded the prize “for pioneering approaches to upcycle plastic waste and remove toxic ‘forever chemicals’ from water by developing reactions and catalysts that selectively control the structure and function of polymers.”

“Frank is an incredible asset to the College of Arts and Sciences and the Carolina community,” said Jim White, the Craver Family Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. “His intuitive scientific insights and passion for service are making an impact on the state of North Carolina and inspiring students, staff and fellow faculty alike. We’re delighted to see him receive this well-earned and remarkable honor.”

Absorbing PFAS

The 2016 finding that per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, better known as PFAS, had been detected in the Cape Fear River Basin shocked the communities that draw their water from the basin. These “forever chemicals” are nearly impossible to break down so they instead accumulate in the environment — and in living tissue, where they can increase the risk of cancer, birth defects and other health issues.

Almost a decade later, researchers across disciplines are still working to make sense of what these chemicals mean for their communities and how to mitigate the risk. Leibfarth joined the fight by drawing inspiration from an unconventional source: diapers.

Leibfarth studies polymers, or long chains of repeating chemical structures that make up materials from plastic and rubber to fingernails and DNA. The absorbent hydrogels inside diapers are also polymers that keep users dry by clinging tightly to liquids. When a colleague asked Leibfarth why no one had made a hydrogel that could soak up PFAS, he set to work designing one.

Although the hydrogel proved highly effective in a laboratory environment, Leibfarth needed help to scale up his resin for use at water treatment plants. Enter the North Carolina Collaboratory, an innovative group based at UNC-Chapel Hill that provides state and private support to projects aiming to better North Carolina through research.

The Collaboratory established NC Pure, a research project embedded in its larger PFAS Testing Network and helmed by Leibfarth and his collaborator Orlando Coronell, a professor of environmental sciences and engineering in the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health and an adjunct professor of applied physical sciences at Carolina. Through NC Pure, Leibfarth, Coronell and their team have conducted pilot tests in four municipal water treatment utilities in North Carolina and provided critical data to inform their decision-making around PFAS management. Leibfarth and Coronell cofounded Sorbenta Inc., a start-up company focused on implementing this PFAS removal technology more broadly.

Revitalizing plastic waste

Plastic is another pollutant accumulating in the environment at an alarming rate. While many types of plastic can be recycled after use, the resulting products are less valuable than their starting materials, making plastic recycling an economically disadvantageous process.

Two of the most common types of plastic, polyethylene and polypropylene, are notoriously difficult to break down in part because of the strong bonds that hold the molecules together. Leibfarth’s expertise in polymer chemistry gives him unique insights into how researchers might modify and rearrange those bonds to produce new, more valuable materials, thereby “upcycling” the plastic waste.

His lab has been working on chemical reagents that can be added to existing recycling workflows to transform the plastic particles instead of simply heating and grinding them. So far, they’ve found some potential reagents, but they’re effective only on pure polyethylene or polypropylene. Mixed plastics and food residue — both common in current recycling pipelines — complicate the process. Leibfarth has collaborated with numerous industrial partners to explore avenues to translate this work from a laboratory environment to a commercial setting, with work ongoing to address key economic and environmental limitations.

With such enterprising ideas, it is easy to see why the Blavatnik Award is far from Leibfarth’s first notable honor. Some of his other accolades include a Sloan Research Fellowship in Chemistry, a Cottrell Scholar Award, the UNC Tanner Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching, a Barry Goldwater Scholarship, a Presidential Early Career Award and being named a “Brilliant 10” early-career scientist by the magazine Popular Science.

Leibfarth, however, is quick to mention the contributions of fellow scientists to his award-winning research. “Since starting at UNC in 2016, I have had the privilege of working with some of the most talented and ambitious scientists internationally who care deeply about making plastics more sustainable and removing forever chemicals from our environment,” he said. “The Blavatnik award recognizes their hard work and dedication during their educational journey.”

Leibfarth continued, “I am especially proud to receive the Blavatnik Award for Young Scientists for work at a state university. Being able to do groundbreaking research that serves the students and citizens of the state is immensely fulfilling and is a responsibility I take seriously.”

Learn more about Leibfarth’s research and get to know the other 2025 Blavatnik laureates.