Older Forever Chemicals Plunge in Blood Tests as New Replacements Quietly Emerge

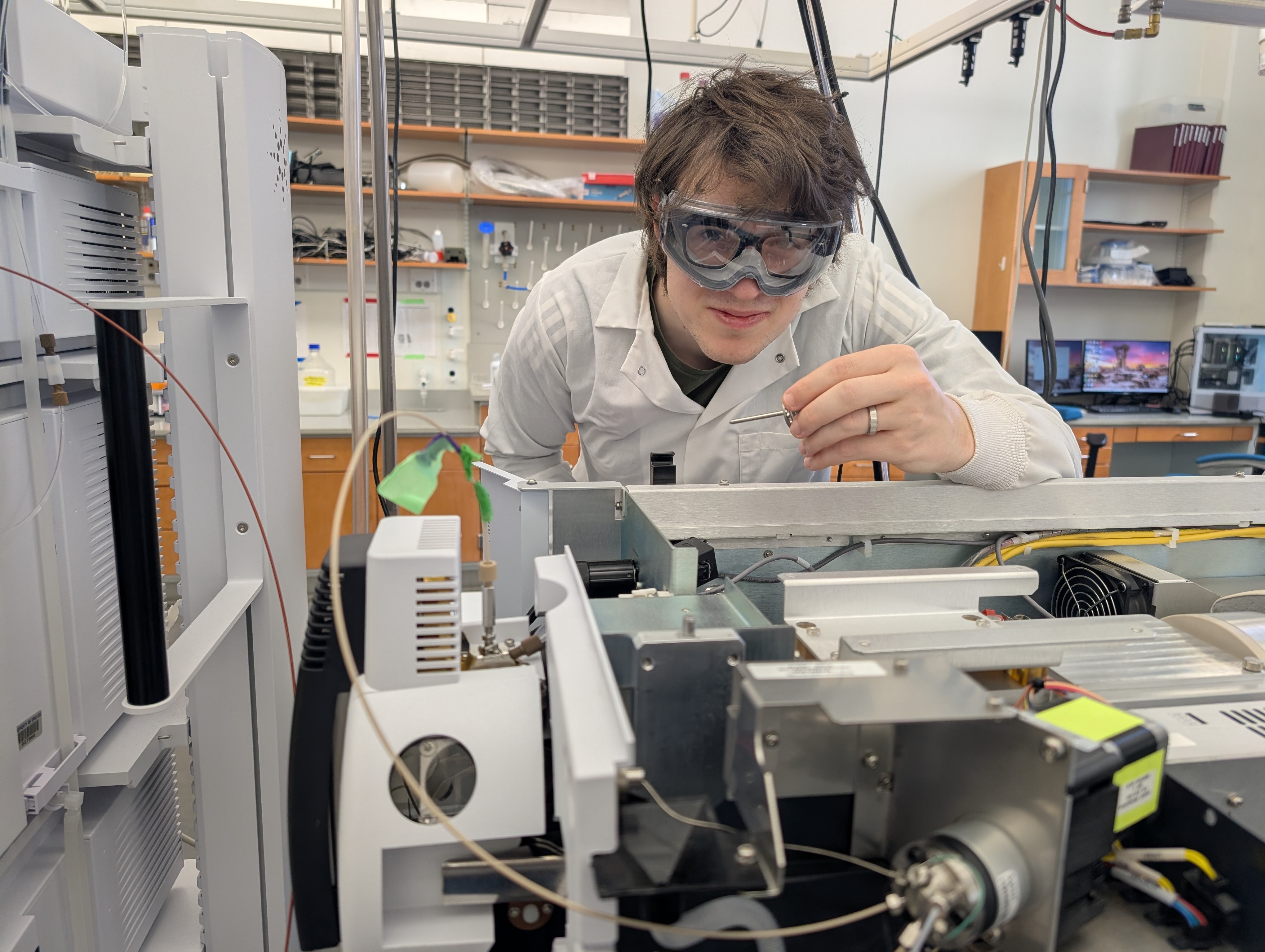

In the study, Gregory Kudzin, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Chemistry, and the UNC-led research team, analyzed the blood serum samples from an NIH-supported study focused on autoimmune diseases, conditions in which the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissue. The researchers wanted to see whether PFAS exposure might be linked to those diseases.

February 13, 2026 I By Dave DeFusco

Researchers in the Department of Chemistry have published a study in Environmental Science and Technology examining how exposure to “forever chemicals” has changed over nearly two decades. The team analyzed 156 human blood serum samples collected over 18 years, looking for both older PFAS now being phased out and newer replacement compounds entering the environment.

These chemicals, known as PFAS—short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances—don’t break down easily in the environment or the human body, allowing them to accumulate in water, soil, wildlife and people. Common in products such as nonstick cookware, waterproof clothing, food packaging and firefighting foam, some PFAS have increasingly been linked to health concerns, including effects on the immune system, cholesterol levels and certain cancers.

To reduce risks, manufacturers in the early 2000s voluntarily began phasing out two well-known PFAS chemicals, PFOA and PFOS. Regulations have also been proposed to limit PFAS levels in drinking water, however newer replacement chemicals have appeared and their health effects remain less understood.

In the study, “Evaluating Legacy and Emerging PFAS in Human Blood Collected from 2003 to 2021,” the UNC-led research team analyzed the blood serum samples from an NIH-supported study focused on autoimmune diseases, conditions in which the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissue. Researchers wanted to see whether PFAS exposure might be linked to those diseases.

“The study was selected with the NIH as part of a large interdisciplinary effort looking at autoimmune disease and environmental exposure,” said Gregory Kudzin, lead author of the study and a Ph.D. student in the UNC Department of Chemistry. “We were asking whether individuals with higher PFAS exposure were more likely to develop autoimmune disease and in the data we had, we didn’t see a clear link.”

Even without a direct disease connection, the study revealed important trends. Older PFAS chemicals, such as PFOS and PFOA, showed a strong decline in human blood levels over time, which matches national monitoring studies. Overall exposure to 10 well-known PFAS dropped by more than 80% from 2003 to 2021.

The picture, however, is not entirely reassuring. Some older PFAS did not decline as clearly, possibly because they were present at low levels that were harder to measure. More important, the researchers found evidence that new types of PFAS are appearing more often in human blood.

Kudzin said that companies have modified PFAS chemistry in two main ways. “One method is making very slight variations on the same basic structure, maybe slightly longer or shorter molecules, so they avoid strict monitoring,” he said. “The other trend is adding features meant to help them break down more easily, such as oxygen atoms or even different halogens like chlorine. That may enable environmental transformation, however, the toxicity of these features is unknown and very hard to trace.”

To capture both known and unknown chemicals, the team used three kinds of testing. Targeted analysis searched for specific, well-studied PFAS. Suspect screening looked for chemicals scientists believed might be present. Non-targeted analysis cast the widest net, allowing the discovery of previously unknown compounds.

That broader search revealed several emerging PFAS, including one called 9Cl-PF3ONS, which has been widely reported in Asia but, to the researchers’ knowledge, had not previously been detected in individuals’ serum in the United States.

“We don’t yet know the source,” said Kudzin. “It could be imported products or domestic manufacturing, but its growing presence raises a flag for future monitoring.”

The researchers also detected newer chemical groups used in food packaging, pesticides and other products. These compounds may break down faster than older PFAS, which can make them harder to measure even if exposure is significant. At the same time, some scientists worry that short-term, acute exposure to these replacement PFAS could pose risks comparable to the long-term buildup seen with legacy PFAS.

Another finding surprised the team: the study population showed higher PFAS levels overall than the U.S. national average reported in government surveys. Kudzin said that could reflect the group’s concentration in metropolitan areas near possible industrial sources, though more research is needed.

Erin Baker, senior author of the study and a professor of chemistry at UNC, said the results highlight both progress and new challenges.

“This research shows that while legacy PFAS are declining, they are being replaced by a complex mix of newer chemicals that we still know very little about,” she said. “Understanding what these replacements are, how widespread they are and what they might do to human health is essential for protecting public health going forward.”