Researchers Use Light to Reshape Molecules in Powerful New Ways

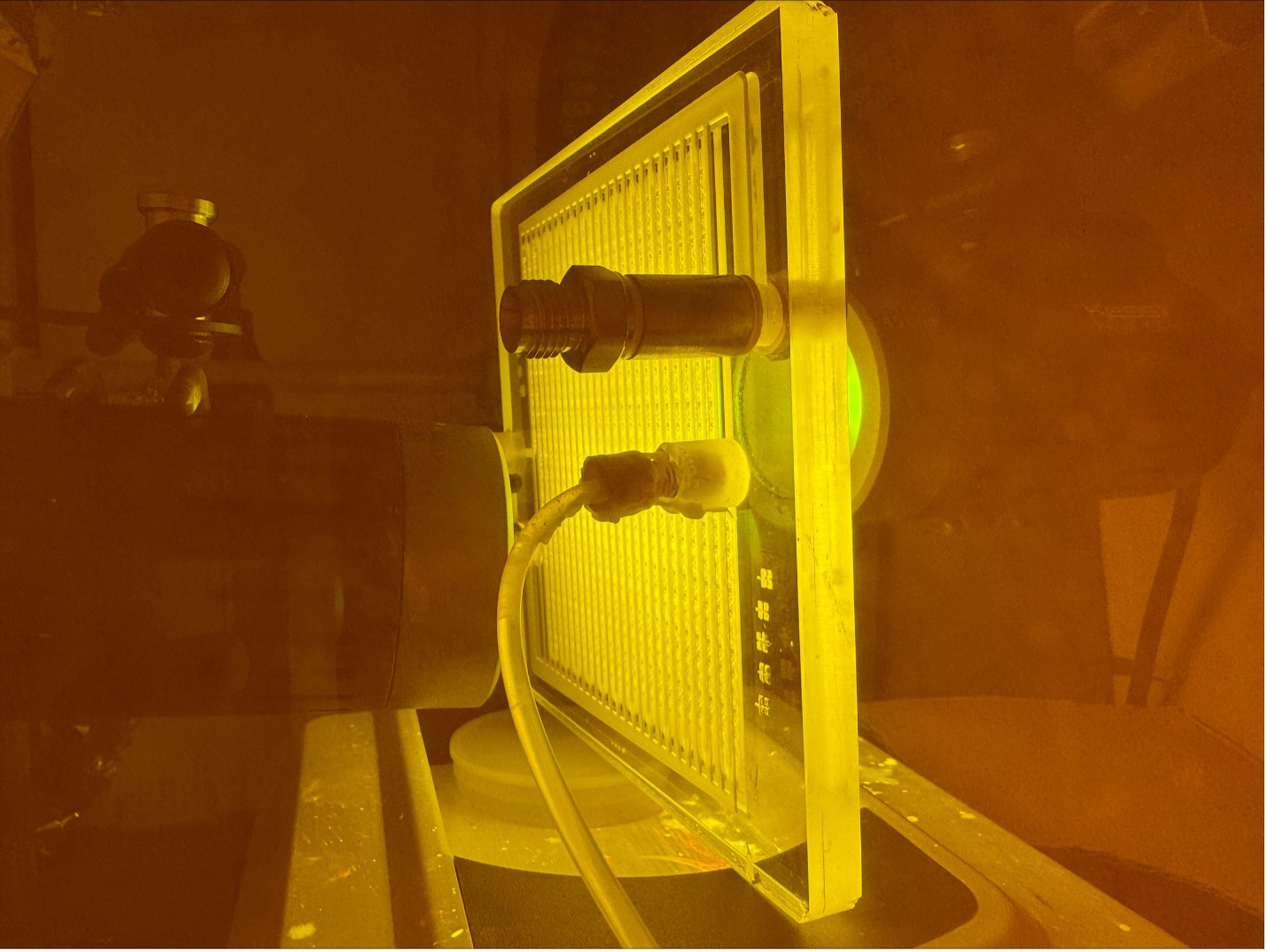

UNC chemists used a flow cell to run light-driven reactions at a large scale. The team tested their method on more than 30 different molecules, many of them designed to resemble structures found in medicinal chemistry.

January 29, 2026 I By David DeFusco

A paper in the journal Chemical Science shows how UNC-Chapel Hill chemistry researchers have found a powerful new way to rearrange chemical bonds using light. The work opens up faster and more flexible ways to build complex molecules that matter for medicine.

The study, “Cation Radical-mediated Semi-pinacol and n+2 Ring Expansions via Organic Photoredox Catalysis,” was led by David Nicewicz, William R, Kenan Distinguished Professor, with key contributions from Ph.D. student Connor Owen and Brandon Fulton, a former postdoctoral researcher in the Nicewicz Lab and now a process chemistry research and development scientist with STA Pharmaceuticals in San Diego.

At its heart, the research uses light to temporarily change the electrical state of a molecule. When blue light shines on a special catalyst, it can remove a single electron from part of a molecule. That creates what chemists call a “cation radical,” a molecule that carries both a positive charge and an unpaired electron. This unstable state can trigger dramatic internal rearrangements.

“These rearrangement reactions are like molecular shortcuts,” said Nicewicz. “They let us take simple, inexpensive starting materials and rapidly turn them into much more complex shapes that would otherwise take many steps to build.”

The chemistry team discovered two closely related but distinct reactions. In one, called a cation radical-mediated semi-pinacol rearrangement, a charged molecule shifts one of its internal groups in a single, coordinated motion. In the other, the molecule takes a step-by-step route that causes a small four-membered ring to expand into a six-membered ring.

“We started out trying to make a light-driven version of a well-known chemistry reaction,” said Fulton. “But then we saw the reaction working in situations where, according to the usual rules, it shouldn’t have worked at all. After drawing out many possible explanations, we turned to computer modeling and realized we hadn’t made just one reaction, we had actually uncovered two different ones.”

The researchers found that light can coax molecules to reorganize their skeletons. In one case, a piece of the molecule slides over smoothly, forming a new carbon-oxygen bond. In the other, light helps break open a strained ring, then allows the pieces to reconnect into a larger, more useful ring shape.

Ring expansions are especially valuable because many drugs and natural products are built around ring systems. Being able to turn a small ring into a larger one in a controlled way gives chemists access to structures that are otherwise hard to make.

The team tested their method on more than 30 different molecules, many of them designed to resemble structures found in medicinal chemistry. They showed that the reaction tolerates a wide range of chemical features, including nitrogen-containing groups, oxygen-containing groups and several common ring systems.

“One exciting aspect is how flexible this chemistry is,” said Owen. “We can easily incorporate these small rings into the molecule and reliably expand them, even when sensitive groups are present.”

The researchers also showed that the reactions work on a practical scale. They successfully ran them on gram-scale quantities, both in standard laboratory flasks and in continuous-flow systems, which are often used in industry.

“It’s really important to provide proof that new reactions are amenable to scale up,” said Fulton, “especially for more modern methods like photo- or electrochemistry that haven’t been fully adopted by industry yet. We need to show that these types of reactions are reliable, predictable and easy to implement.”

Beyond making new molecules, the team wanted to understand why the reactions behave the way they do. They combined laboratory experiments with computer calculations to map out the possible reaction pathways.

Their results suggest that some molecules rearrange in a single, concerted step, while others follow a longer sequence involving electron transfer, bond breaking, ring opening and hydrogen atom movement. Which route is taken depends on how the charged part of the molecule is oriented relative to the alcohol group that starts the process.

“This kind of mechanistic insight is critical,” said Owen. “If we understand how each step of these reactions work, we can use the information to strategically design novel transformations.”

Rearrangement reactions have long been a staple of organic chemistry, but charged radical versions have been much less explored. By showing that cation radicals can reliably drive these transformations under mild, light-driven conditions, the UNC team has expanded the chemist’s toolbox.

“Our goal is to give synthetic chemists more options,” said Nicewicz. “If you can quickly reshape a molecule using light, that changes how you plan a synthesis from the very beginning. It’s exciting to see how a simple idea—using light to move electrons—can unlock so many new possibilities.”