Microscopic Animals Use Mitochondrial Signal to Survive Extreme Stress

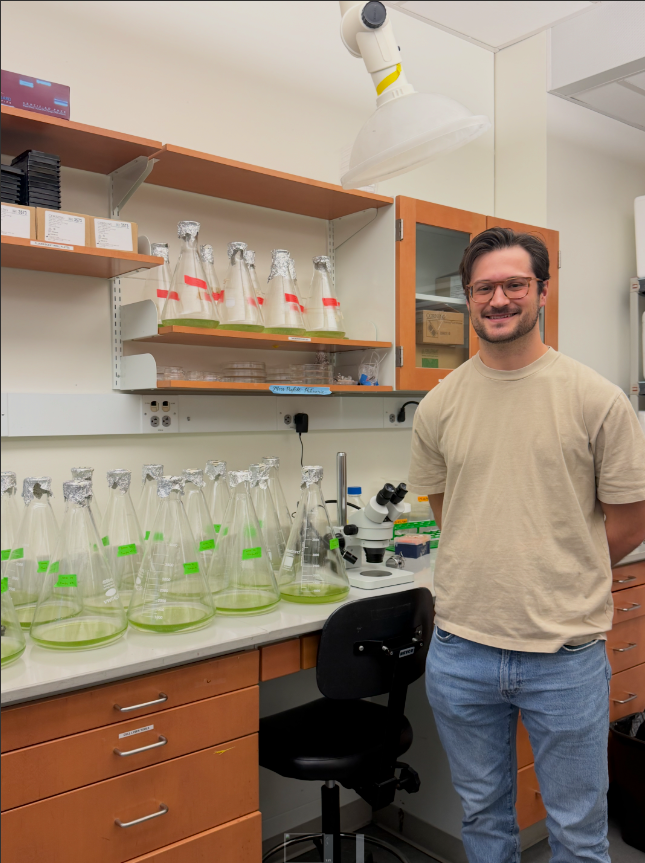

Evan Stair, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Chemistry, is one of the lead authors of a study that investigated how tardigrades, nature’s apocalypse champions, survive osmotic stress.

December 16, 2025 | By Amie Solosky

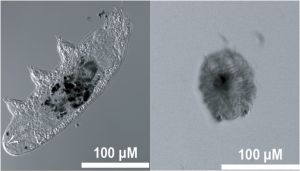

Evan Stair, a chemistry Ph.D. student in the Hicks Lab, spends his days feeding and studying water bears, or tardigrades, which are one of the most indestructible animals to exist. These microscopic creatures can survive freezing temperatures, irradiation and even the vacuum of space, and Stair and his co-author, Brendin Flinn from the Kolling Lab at Marshall University, have proposed one of the first biological mechanisms showing how these tiny water bears do it.

Published in the Journal of Proteome Research, “Mitochondria-Derived Reactive Oxygen Species Regulation of Tardigrade Osmobiosis Revealed by Proteomics of Hypsibius exemplaris,” the researchers describe how tardigrades are able to survive in a specific condition, known as osmotic stress. Osmotic stress happens when there is too much of a certain solute, like salt or sugar, where there is some moisture, such as in wet moss, puddles, soil and even freshwater sediments.

This study not only reveals how tardigrades are able to withstand such extreme stress on the biological level but also paves the way for scientists to use this knowledge for other important issues such as cell preservation, engineering resilient crops and even designing safer cancer treatments.

“Tardigrades may live in these shallow pools of water in their environment that dry up and increase the concentrations, causing them to go into tuns,” said Stair. Tuns is a state that is only available to tardigrades when they are going into extreme survival mode. When this state occurs, their bodies completely cave in, they expel all the extra water in their bodies and go into hibernation. They can stay in this state for decades.

This process is akin to when a human is in the bath for too long and their fingers prune, except the tardigrade needs the water to not evaporate. Since over time the water where tardigrades live will eventually evaporate, the water bear may find itself stuck in a puddle that is drying faster than they can escape it. This leaves them vulnerable to high concentrations of salt or other solutes that will not evaporate as quickly, if ever. Most animals would die, but tardigrades instead hibernate until the salt levels become safe again.

To figure out how tardigrades survive osmotic stress, the researchers analyzed proteins tardigrades turn on during their hibernation state. Proteins drive all kinds of distinct functions in the body and can inform the biology going on at the cellular level. The two researchers did this by placing tardigrades in both high-sugar and high-salt environments to induce osmotic stress. Their experiments revealed that many of the proteins expressed in this state are related to mitochondria—the powerhouse of the cell.

“We found that their ability to survive extreme stress is an active process. For a long time, scientists thought it was passive. That water just rushed out of their bodies whenever they went into their survival state,” said Stair. “Our work has shown that it requires signaling from the mitochondria and they change this signaling based on if it is sugar or salt, indicating that they know the difference.”

An example of one of the proteins they found from tardigrades in osmotic stress is called peroxiredoxin, an antioxidant protein that protects cells from excessive harmful molecules called reactive oxygen species. Although humans can make this protein, tardigrades take advantage of it in a way that humans do not. Stair proposed that they use it to prevent cell death, adding one piece to the puzzle of how these microscopic water bears can withstand more stress compared to humans. Understanding the tardigrade’s mechanisms of survival have big picture implications as well, with several of the applications in medicine and even agriculture.

“Tardigrades can survive being completely dehydrated. If you think about plants during droughts, if we could harness the ability from tardigrades to survive that, we could apply it to plants to make them more drought-tolerant,” said Stair.

Similarly, tardigrades can survive irradiation, which could be useful in designing radiation treatments for cancerous tumors that are less harmful to the rest of the healthy cells in the body.

“We are still on the discovery side because there is still a lot not known about these creatures; and in the literature, there hasn’t been a lot of proteomics work done,” said Stair. “One of the big challenges when I started this research was creating reproducible proteomics workflows. Now we have the methods to do it.”