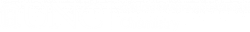

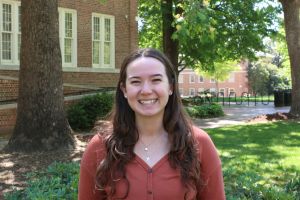

Justine Drappeau Balances Breakthrough Science with Big-Hearted Leadership

Justine Drappeau isn’t just a rising star in one of chemistry’s most dynamic research areas—she’s also a mentor, leader, teacher and advocate, balancing complex lab work with a deep commitment to helping others grow.

June 10, 2025 I By Dave DeFusco

When Justine Drappeau arrived at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for her Ph.D. in chemistry, she didn’t expect to become a trailblazer in something called C–H functionalization. In fact, she hadn’t even heard of it. “I was doing very different research in undergrad,” she said. “Then I came across Professor Erik Alexanian’s website and thought, ‘Wow, this is super cool.’”

Fast forward to today: Drappeau isn’t just a rising star in one of chemistry’s most dynamic research areas—she’s also a mentor, leader, teacher and advocate, balancing complex lab work with a deep commitment to helping others grow.

At the heart of Drappeau’s research lies a deceptively simple question: What if we could build new molecules not by tearing everything apart and starting from scratch, but by making tiny changes to what we already have? That’s the promise of C–H functionalization, a technique that tweaks one of the most common types of chemical bonds—the carbon–hydrogen bond—by adding useful new parts.

“Traditionally, if a drug company wanted to build a library of related compounds, they’d have to go through a long, multistep process,” said Drappeau. “That wastes time, resources and atoms. With C–H functionalization, we can make those changes directly, faster and more efficiently.”

But the process isn’t without its hurdles. One major challenge is regioselectivity, or how to control where on a molecule the change actually happens. When molecules have multiple carbon-hydrogen bonds that look alike, how do you choose the right one? Add to that the presence of sensitive groups, like alcohols or amines, that tend to interfere, and things can get messy fast.

Her breakthrough came by exploring an unusual helper: HFIP, or hexafluoroisopropanol, a solvent with unique hydrogen-bonding abilities. “I was curious whether HFIP could influence which C–H bond got functionalized,” she said.

Using HFIP in reactions helped suppress unwanted changes near alcohol groups and nudged the chemistry toward more selective outcomes. In one case, she worked with a compound called menthol—famously tricky due to its reactive parts—and managed to direct the transformation to just one spot. No protection steps needed. No messy mixtures. Just precision.

In another project, Drappeau used a similar approach to build α-ketoesters, valuable ingredients in drugs and natural products. By generating specialized radicals that selectively attach to benzylic sites—locations on molecules with high relevance in medicine—she produced complex structures under mild conditions with remarkable accuracy. Her method worked even when the molecules had other sensitive parts, like free acids or aldehydes, and it required no excess starting material—a common limitation in similar strategies.

“Justine has developed several unique, site-selective C–H functionalizations applicable to a wide range of valuable small molecules,” said Dr. Erik Alexanian, Drappeau’s advisor and a professor in the Department of Chemistry.

If her science is about transformation, so is her leadership. As co-president of Industry InSight, Drappeau helped organize a high-impact networking symposium connecting over 110 graduate students with industry professionals from 12 diverse companies.

“A lot of grad students don’t realize how many career options are out there,” she said. “We wanted to bridge that gap and show them how their skills apply beyond just academia.”

She also chairs the Graduate Committee for Professional Development, where she leads initiatives ranging from company visits to seminars on resumes and interviews. She even finds time to mentor undergraduates and incoming Ph.D. students, teach organic chemistry labs and has led a team in WinSPIRE, a program that recruits high school girls into science research.

As she nears the completion of her Ph.D., Drappeau is starting to think about life after UNC. Industry, with its fast pace and applied focus, appeals to her—but whatever path she chooses, she’ll be a catalyst—for science, for colleagues and for a better way to get the most out of both of them.

“She’s the kind of person who raises the bar for everyone around her,” said Professor Alexanian.